The Biblioteca Antonelliana boasts no less than 11 incunabula, or books printed before 1500 (“in the infancy of the art”, as the Oxford English Dictionary charmingly puts it). I decided to look at the two singled out by Marinella Bonvini Mazzanti in her “Senigallia” (Urbino: QuattroVenti, 1998). She chose first Livy’s History of Rome.

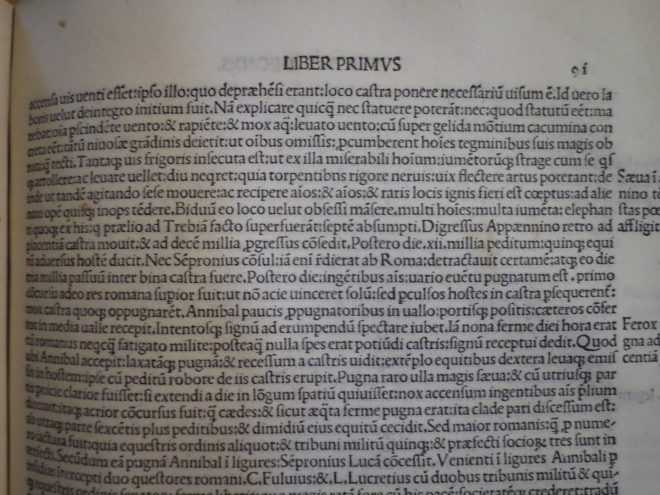

I thought you’d like a passage about the elephants. This is from Book 21, chapter 58. Hannibal is crossing the Apennines, nearly as bad as the Alps and bitterly cold. Seven elephants died (lines 8-9). So much for sunny Italy! Note that a little line above a letter is an abbreviation, such as scribes used to use, often standing for n or m.

This edition was printed in Venice in 1491 by Johannes Rubeus Vercellensis or Matteo Capcasa. I love its beautiful, clear, elegant typeface. Capcasa has already popped up in my first blog post, “On the trail of incunabula in central Italy“, this time as printer of a prologue to the letters of Marsilio Ficino, though by 1495 Capcasa had moved to Parma.

What makes this edition a bit different is its editor, Marcus Antonius Coccius Sabellicus (1436-1506), whose original Italian name was Marcantonio da Coccia. Marcantonio, a blacksmith’s son, is an interesting person in his own right. From his humble origins, he rose to become a humanist and professional man of letters. He is the owner of the first known European copyright, granted to him in 1486 by the Venetian government.

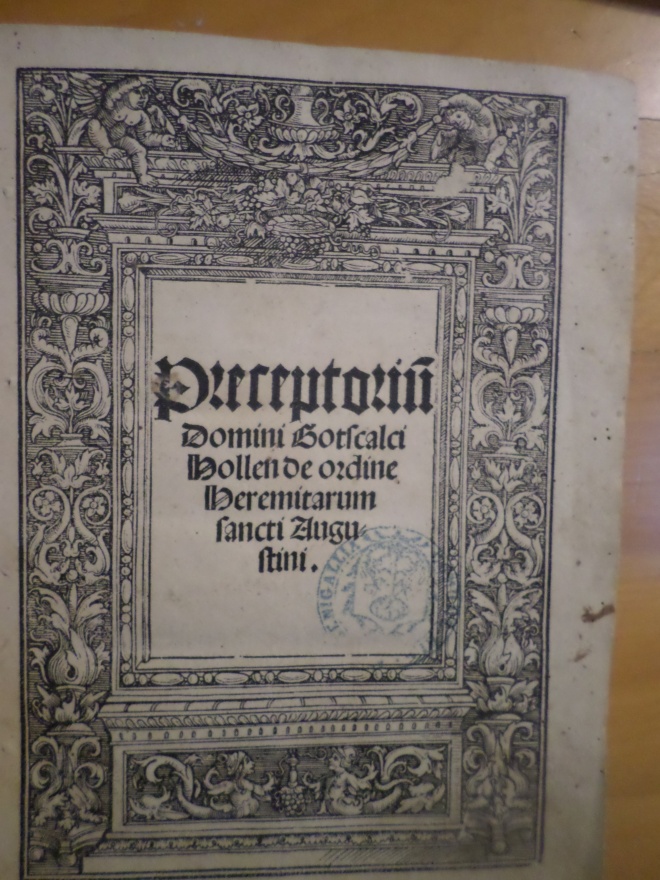

Mazzanti’s next choice of book is a complete contrast – from classical humanism to traditional theology.

This is one of those late fifteenth-century theological works which an English librarian described to me, somewhat disparagingly, as relatively common among incunabula. Hollen (c1411-1481) was a German theologian and preacher. This book is a work of instruction in moral theology for laymen and priests alike, though principally aimed at helping priests in their pastoral duties. Hollen wanted to save them a bit of trouble in writing their sermons.

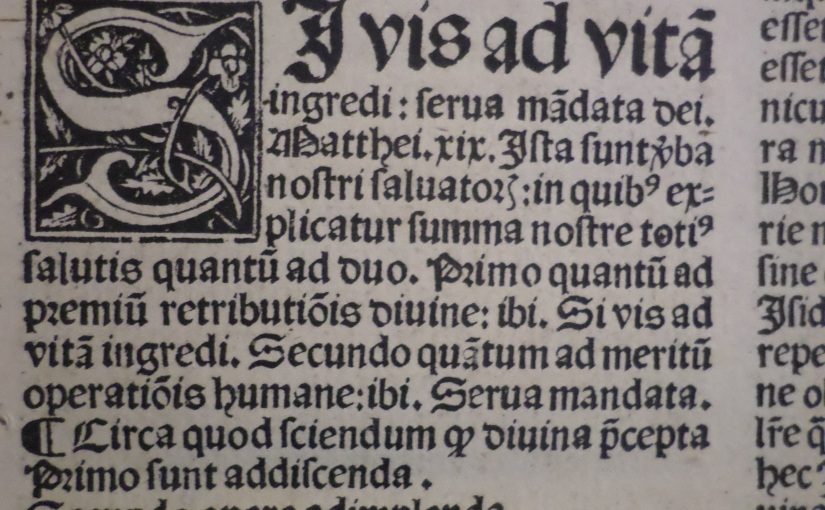

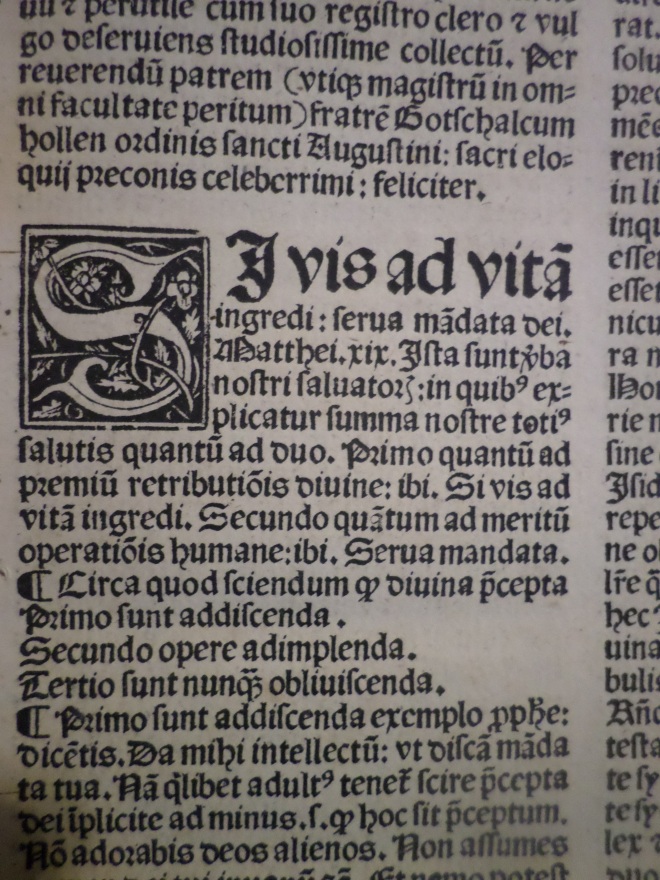

I wanted to show you the “illuminated” S. Early printed books were often decorated in this way to appeal to potential buyers, who were used to attractively illuminated manuscripts. The page above is a sample sermon on the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 19, verses 16-22, the story of the rich young man who could not bring himself to give up his great possessions for the sake of eternal life. The passage begins, “If you wish to enter life, keep God’s commandments.”

The bibliographical details of this work are a bit of a puzzle. According to Mazzanti, the ISTC and the staff of the Biblioteca Antonelliana, this is one of only two copies in Italy (the other is in Fabriano) of a 1491 edition, printed in Nuremberg for Anton Koberger in 1491. But in Mei’s “Collectio Thesauri”, vol I, Simonetta Pirani describes it as a 1521 edition. I can’t resolve the difference because the colophon has been carefully cut out by some unscrupulous person. (In early printed books the printer’s details were contained in a colophon at the end of the book.) There is only a modern pencilled note giving the 1491 details.

I hope this post will encourage you to visit local libraries in the Marche and ask to see their early printed books. They are usually very helpful if you ring or call in advance (contact details are usually on the comune’s website), but their English may not be fluent. Probably your local comune, wherever you are staying or wherever you live in the region, will have some treasures in its library.