Sums it all up. I didn’t know these lines until I discovered them on Luigi Maria’s blog. Thank you, Luigi!

The Englishwoman visits Senigallia’s Biblioteca Antonelliana. Part III: Early printed books.

The Biblioteca Antonelliana boasts no less than 11 incunabula, or books printed before 1500 (“in the infancy of the art”, as the Oxford English Dictionary charmingly puts it). I decided to look at the two singled out by Marinella Bonvini Mazzanti in her “Senigallia” (Urbino: QuattroVenti, 1998). She chose first Livy’s History of Rome.

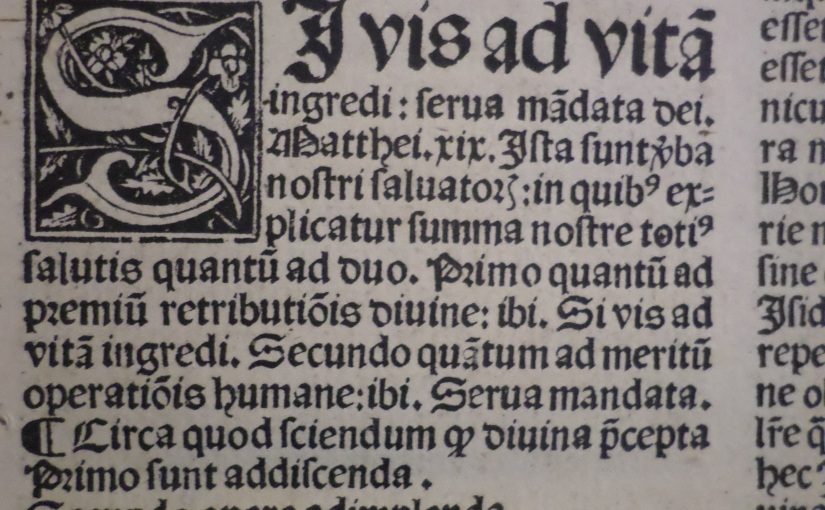

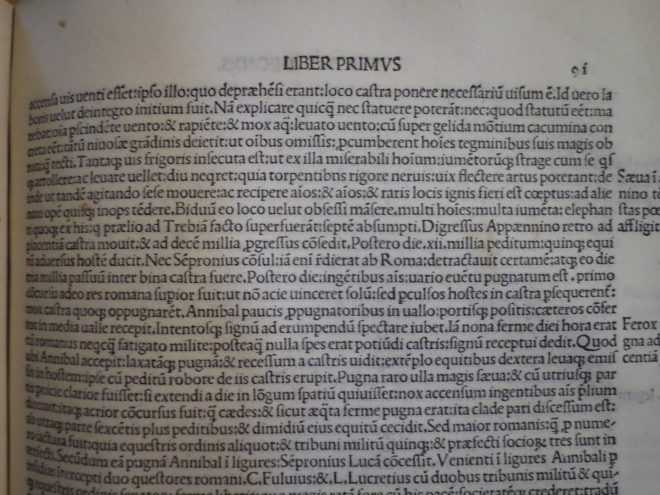

I thought you’d like a passage about the elephants. This is from Book 21, chapter 58. Hannibal is crossing the Apennines, nearly as bad as the Alps and bitterly cold. Seven elephants died (lines 8-9). So much for sunny Italy! Note that a little line above a letter is an abbreviation, such as scribes used to use, often standing for n or m.

This edition was printed in Venice in 1491 by Johannes Rubeus Vercellensis or Matteo Capcasa. I love its beautiful, clear, elegant typeface. Capcasa has already popped up in my first blog post, “On the trail of incunabula in central Italy“, this time as printer of a prologue to the letters of Marsilio Ficino, though by 1495 Capcasa had moved to Parma.

What makes this edition a bit different is its editor, Marcus Antonius Coccius Sabellicus (1436-1506), whose original Italian name was Marcantonio da Coccia. Marcantonio, a blacksmith’s son, is an interesting person in his own right. From his humble origins, he rose to become a humanist and professional man of letters. He is the owner of the first known European copyright, granted to him in 1486 by the Venetian government.

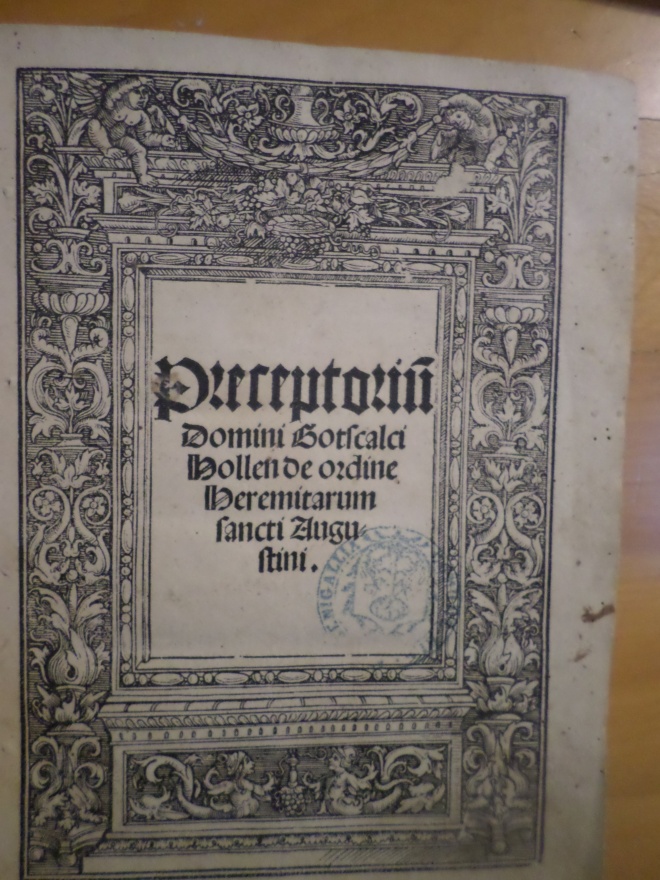

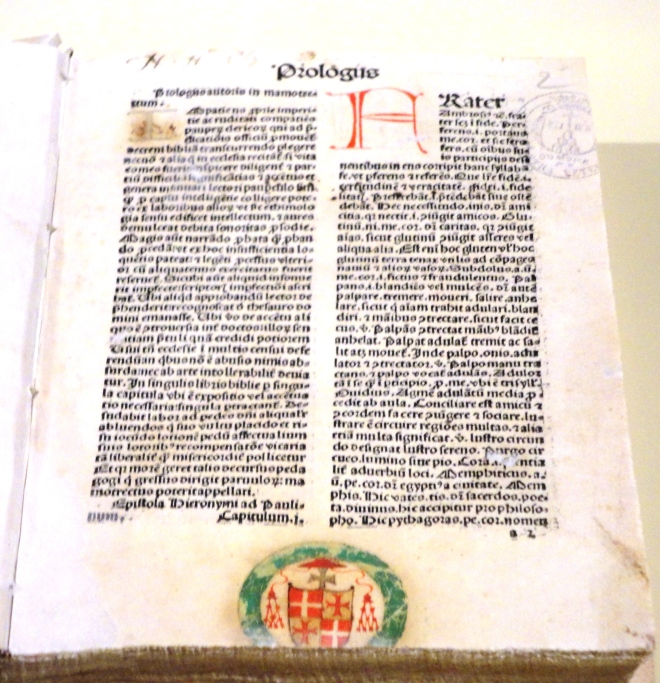

Mazzanti’s next choice of book is a complete contrast – from classical humanism to traditional theology.

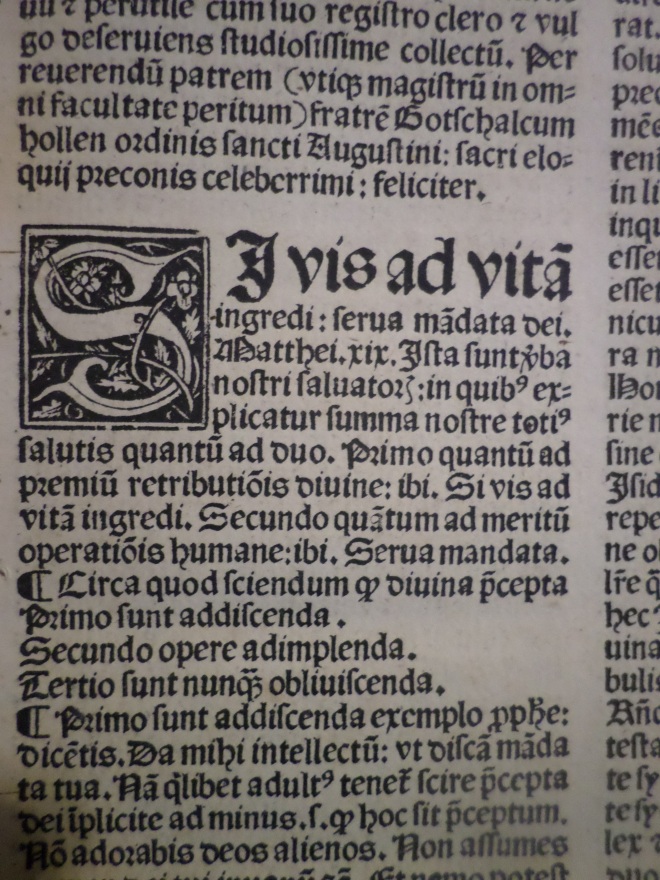

This is one of those late fifteenth-century theological works which an English librarian described to me, somewhat disparagingly, as relatively common among incunabula. Hollen (c1411-1481) was a German theologian and preacher. This book is a work of instruction in moral theology for laymen and priests alike, though principally aimed at helping priests in their pastoral duties. Hollen wanted to save them a bit of trouble in writing their sermons.

I wanted to show you the “illuminated” S. Early printed books were often decorated in this way to appeal to potential buyers, who were used to attractively illuminated manuscripts. The page above is a sample sermon on the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 19, verses 16-22, the story of the rich young man who could not bring himself to give up his great possessions for the sake of eternal life. The passage begins, “If you wish to enter life, keep God’s commandments.”

The bibliographical details of this work are a bit of a puzzle. According to Mazzanti, the ISTC and the staff of the Biblioteca Antonelliana, this is one of only two copies in Italy (the other is in Fabriano) of a 1491 edition, printed in Nuremberg for Anton Koberger in 1491. But in Mei’s “Collectio Thesauri”, vol I, Simonetta Pirani describes it as a 1521 edition. I can’t resolve the difference because the colophon has been carefully cut out by some unscrupulous person. (In early printed books the printer’s details were contained in a colophon at the end of the book.) There is only a modern pencilled note giving the 1491 details.

I hope this post will encourage you to visit local libraries in the Marche and ask to see their early printed books. They are usually very helpful if you ring or call in advance (contact details are usually on the comune’s website), but their English may not be fluent. Probably your local comune, wherever you are staying or wherever you live in the region, will have some treasures in its library.

The Englishwoman visits Senigallia’s Biblioteca Antonelliana. Part II: Corinaldo’s churches.

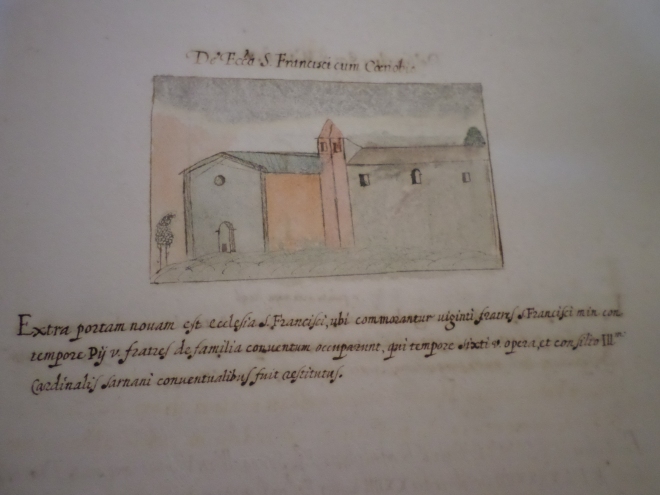

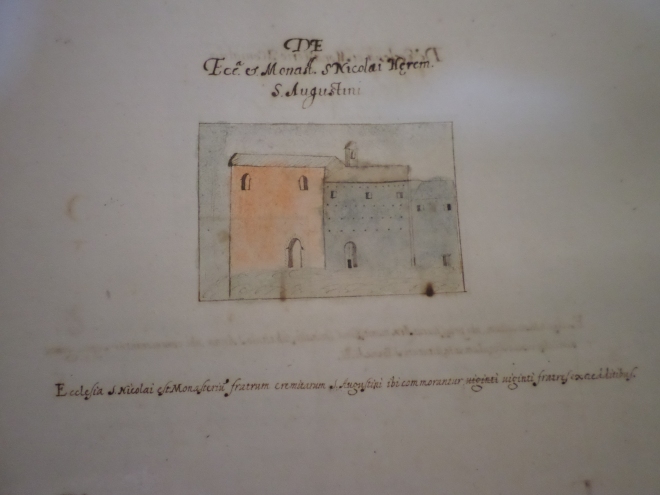

I was fascinated by the difference between Gherardo Cibo’s illustrations, in Ridolfi’s manuscript, of the churches of Corinaldo (where we have our holiday home), and how they appear today. Here are the churches I know best.

Once upon a time San Pietro was Corinaldo’s principal church; now only its bell tower remains.

San Francesco, now Corinaldo’s parish church, formerly attached to a friary of Franciscan Friars Minor. It has been considerably altered since 1596.

This was originally the church of San Niccolò. When it was taken over by the Augustinians, it became known as Sant’Agostino, and is now the Diocesan Sanctuary of Santa Maria Goretti, Corinaldo’s own local saint, who died in 1902 as the result of an attempted rape by a neighbour’s son. Today’s church (below) is not the church Ridolfi knew; that church was mediaeval. The church we see today was built in 1740-56.

The former San Niccolò today.

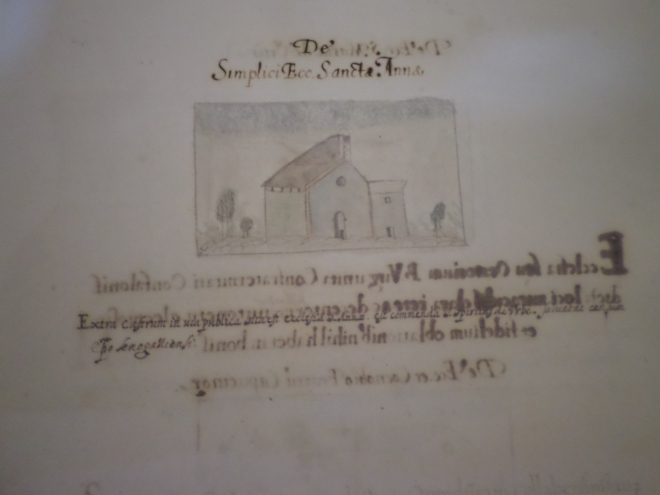

This is the church of Santa Anna, the patron saint of Corinaldo. It’s my favourite of the town churches. It contains a tender late 15th-century wall-painting of Saint Anne, which perhaps Ridolfi knew, with her daughter Mary sitting on her knee, and baby Jesus sitting on Mary’s knee in his turn. The church exudes a sense of love, especially on St Anne’s feast day when it is full of people praying and lighting candles, perhaps in memory of their mothers and grandmothers.

Today’s church is in the same place but was built in the eighteenth century.

Sant’Anna today.

This is the church of Santa Maria “de Ulmis magnis”, “of the big elms”, and you can see an elm in the picture. It is first mentioned in 1090, when it was known as Santa Maria delle terre. The area is still known as Olmigrandi, but the church’s dedication changed to Sant’Apollonia in the eighteenth century, and two centuries later it was demolished and rebuilt a short way down the hill, in 1914. It’s of special interest to me because it’s our local church and we often go to Mass there.

Sant’Apollonia today.

Next time I’ll tell you about the early printed books in the Biblioteca Antonelliana.

The Englishwoman visits Senigallia’s Biblioteca Antonelliana. Part I: Manuscripts.

Senigallia is a pleasant resort town. As well as its lively Lungomare (Promenade) and its Spiaggia di Velluto (velvet beach), it boasts an attractive old town and a fine communal library.

It is much easier to explain face to face, rather than on the telephone, who I am; a British librarian, and what I want to do; spread awareness of the bibliographic treasures of Le Marche. So it was easy to book an appointment to look at some of the manuscripts and rare books in Senigallia’s library, and return a day or two later, as Senigallia is just down the road from us. The staff were most welcoming and helpful. The conditions were not the best for photography, but I thought you’d like to see the manuscripts anyway.

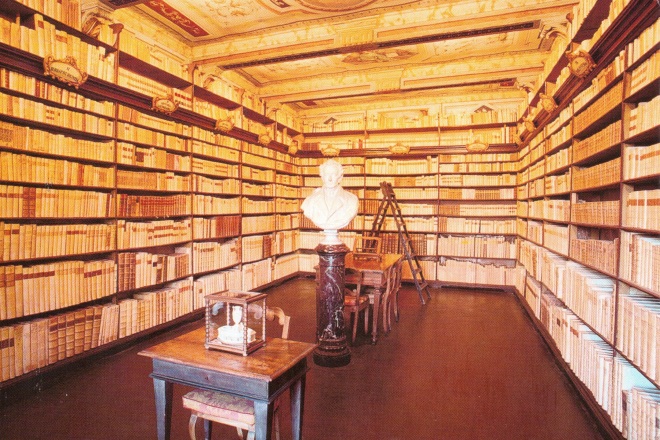

The Biblioteca Antonelliana is called after Cardinal Antonelli, its founder, who in 1767 left all his books to the public administration of Senigallia, for the opening of a public library. His heirs contested the will and it was not until 1825 that the library opened. Since then it has acquired the libraries of various suppressed religious orders, and benefited from the wills of local citizens, both priests and aristocrats.

The library possesses not only books but manuscripts, and I was privileged to be allowed to see some of its greatest treasures.

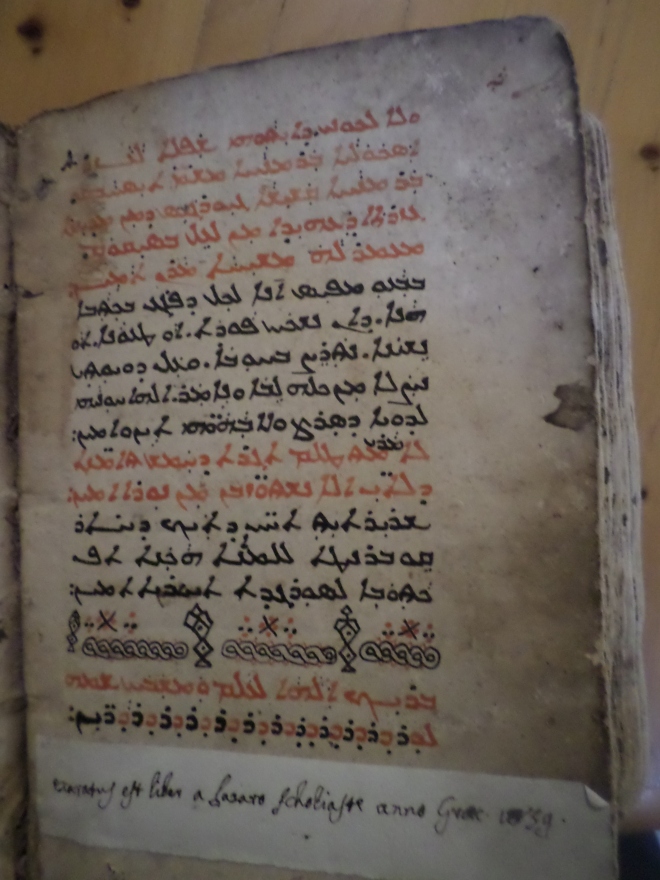

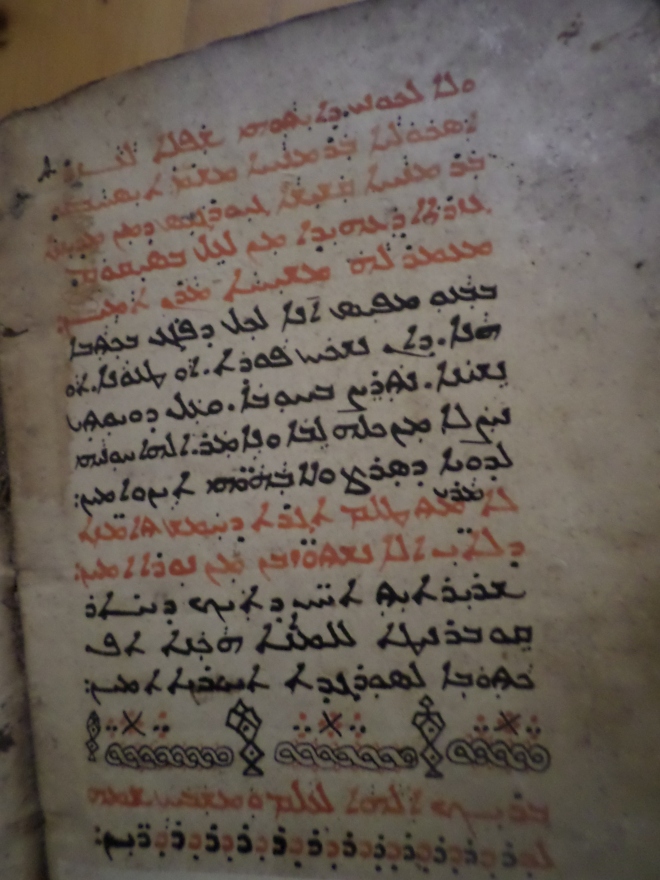

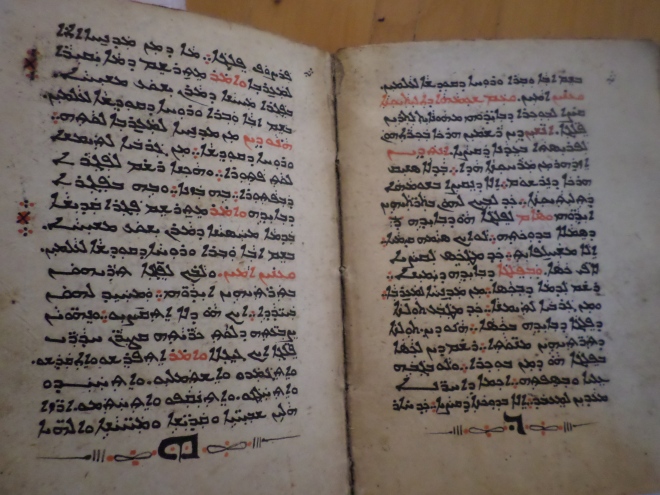

This manuscript is, according to the catalogue, Patriarch Joseph III’s Chaldean missal with the Nestorian liturgy. Presumably this was Patriarch Yosep III Maraugin, who was in office from 1714-57 (or -59), and could therefore have known Antonelli. Apparently the Patriarch had a copy made from a thirteenth-century original used by the “heretical patriarch Elias, whose name can be read” . It is not clear to me whether this is the original or the copy.

Here are four pages from the liturgy.

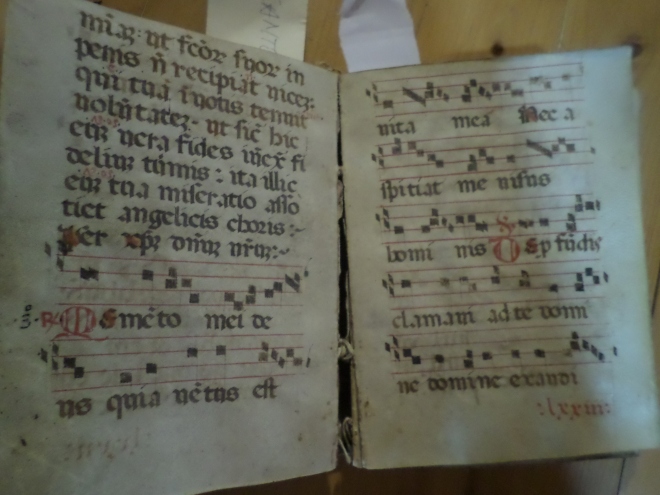

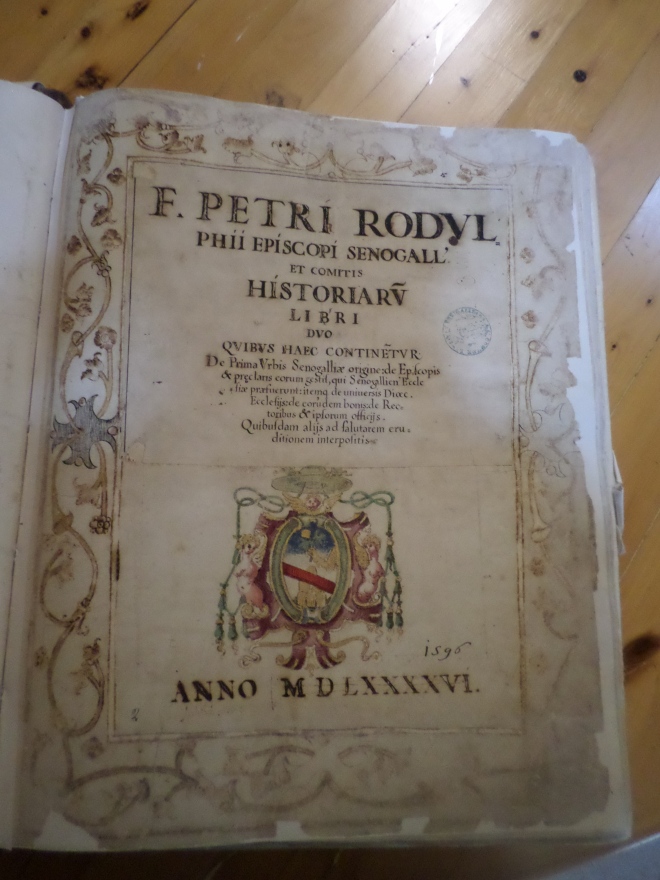

This is a 14th century cantorino of the Office of the Dead. A cantorino is a book of liturgical chants with music. The script is Bolognese Gothic, which was in use in Italy from the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries.

Translation: “that he be not made to suffer for any wrong he may have done; for he always desired to do Thy will. And as the true faith numbered him here among those who served Thee, so let thy mercy find him hereafter a place among the choirs of Angels.

O God be mindful of me, for that my life is but wind, nor the sight of man may behold me.

V: From the depths I did cry to thee O Lord, O Lord hear [my voice]. ”

Translation. “A vow [shall be paid to Thee] in Jerusalem. Hear my prayer. All flesh comes unto thee. Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord, and may perpetual light shine on them.”

![[Blessed is he] who cometh in the name of the Lord. Office of the Dead. Biblioteca Antonelliana Senigallia.](https://beautifulbooksinitaly.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/blessed-is-he-who-cometh-in-the-name-of-the-lord-office-of-the-dead-biblioteca-antonelliana-senigallia.jpg?w=660)

Translation. ” [Blessed is he] who cometh in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest. Lamb of God, who takest away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us. Lamb of God, who takest away the sins of the world, receive our prayer. Thou who sittest at the right hand of the Father, have mercy upon us. Thou only art holy, thou only …”. You can see that there are two different hands here, and it looks as if , in an attempt to substitute a missing page, the Agnus Dei (well over halfway through the Mass) and the Gloria (near the beginning) have got mixed up.

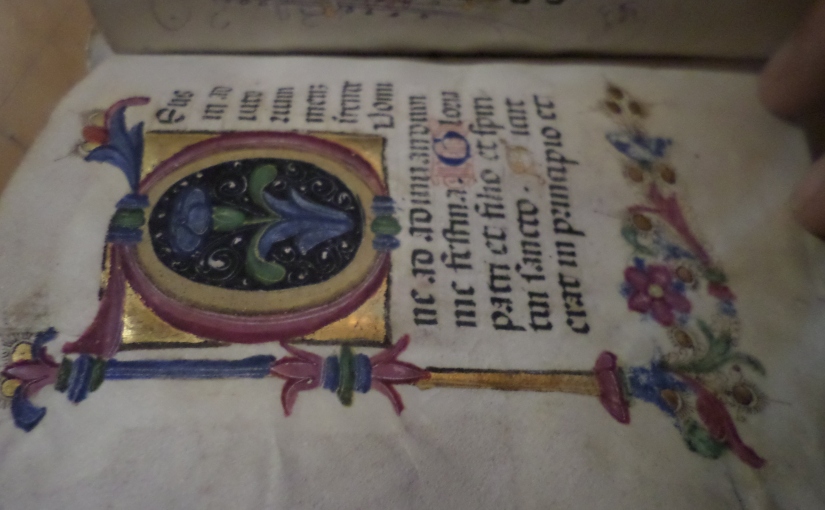

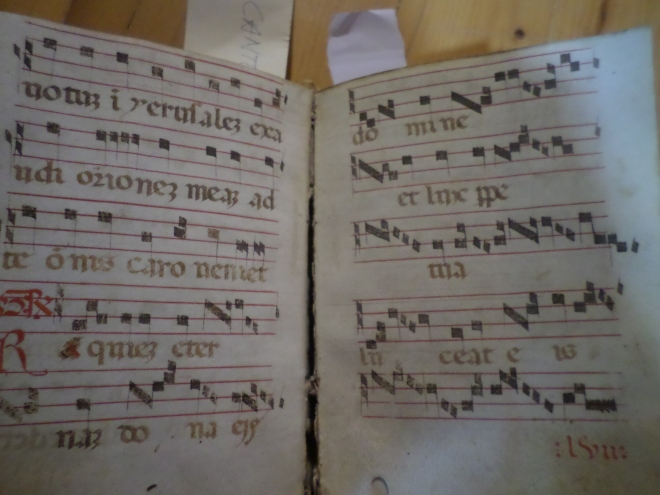

Below is a fifteenth-century illuminated Book of Hours, a collection of devotional text for private use by the laity. Its central nucleus is the Hours of the Blessed Virgin. The script is Gothic Rotunda, in use in Italy, southern France and Spain from the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries. This photograph shows an illuminated D.

Translation: “O God make speed to save me: O Lord make haste to help me.Glory be to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Ghost. As it was in the beginning [is now, and ever shall be].”

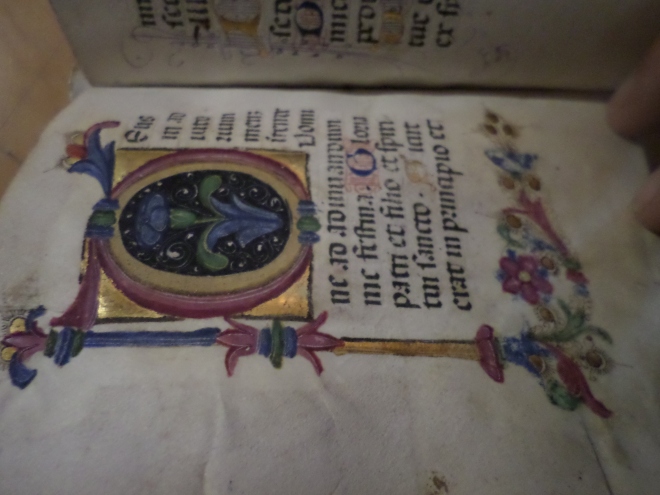

The last manuscript I saw was Bishop Pietro Ridolfi da Tossignano’s “Historiarum libri duo” (Two volumes of histories) which, as well as a history of Senigallia, contains the results of his episcopal visitation, or inspection, of its diocese. According to Marinella Bonvini Mazzanti in Volume 1/1 of “Collectio thesauri”(the exhibition catalogue of the treasures of Le Marche’s libraries), Ridolfi, a man of the Counter-Reformation, was actuated by a passionate desire to revive the spiritual life of the diocese and, presumably, to rescue its churches from neglect. He describes all the places of worship in the diocese, including Corinaldo, with illustrations by Gherardo Cibo and two others. Thus Ridolfi’s work has become an invaluable historical document.

Here is its title page.

In fact the book was probably actually finished in 1601, the year of Ridolfi’s death, so he never had it printed. It has now actually been printed in August of this year, but the official launch is planned for later this month (September).

I didn’t see any more manuscripts but next time I’ll tell you about the early printed books in the Biblioteca Antonelliana.

The Englishwoman visits the Leopardi Library/Biblioteca Leopardi

This library has survived intact for over 200 years thanks to Giacomo Leopardi (1798-1837), one of Italy’s best-loved poets. He spent the greater part of his childhood and youth reading in this library, the creation of his father, Monaldo Leopardi.

The Italian class system is not the same as ours; however, I think it is safe to say that the Leopardi were what we would call gentry, and quite comfortably off. Monaldo was an “avid book collector” (p 363 of Canti / Giacomo Leopardi ; translated and annotated by Jonathan Galassi. London : Penguin, c2010). In fact he spent so much money on this library that his wife had to sell her jewellery to restore the family fortunes.

I like Monaldo because he was more than a bibliophile. His instincts were those of a librarian; in other words, he wanted to share his books with everyone.

![To children friends citizens Monaldo Leopardi [gives] the library in the year 1812](https://beautifulbooksinitaly.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/filiis-amicis-civibus-dedication-by-monaldo-leopardi-of-his-library.jpg?w=660)

This was Giacomo’s favourite room, from whose window he could see the bustling piazza and see and hear Teresa (whom he called Silvia), a maidservant, weaving and singing. Have a look at my other blog for more about this.

Monaldo took advantage of the Napoleonic suppressions of religious houses in Rome to offer a temporary home to their books, many of which he bought when they were being sold off by the authorities. He remarked that the two French occupations of Rome (1798-99 and 1809-14) were “tempo felicissimo per l’acquisto dei libri, perché se ne mise in commercio una massa immensa, spettante non solo a i conventi soppressi, ma a cardinali, prelati, avvocati e gente di ogni classe [a most fortunate time to buy books, because there was a vast mass of them on the market, belonging not only to the suppressed convents, but to cardinals, prelates, lawyers and people of every class]” .He said he would give the books back when the convents and monasteries re-opened, but somehow he never did. He was in good company – a lot of manuscripts and books went to the Vatican, and the most valuable ones are still there. I found this out at a conference I went to in 2012 – here is the link for those who are interested. http://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/122187/2012_MonasticABSTRACTS.pdf

There are a number of incunables in Monaldo’s library, which are not on display, presumably because most visitors are interested in his son the poet and the books he used. However, I searched for Recanati in what my readers already know is my favourite catalogue, the British Library’s Incunabula Short Title Catalogue, and found this:

Juvenalis, Decimus Junius

Title: Satyrae (Comm[entators]: Antonius Mancinellus; Domitius Calderinus; Georgius Merula; Georgius Valla)

Imprint: Venice: Johannes Tacuinus, de Tridino, 24 July 1498 [Giovanni Tacuino]

For a reproduction of the title page follow this link: https://download.digitale-sammlungen.de/pdf/1472833879bsb00054972.pdf and scroll down.

The guide took pains to point out to us the “Prohibiti” section. These are books on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum”, i.e.forbidden by the Roman Catholic church, but Monaldo had obtained permission not only to possess them but for himself and his family to read them.

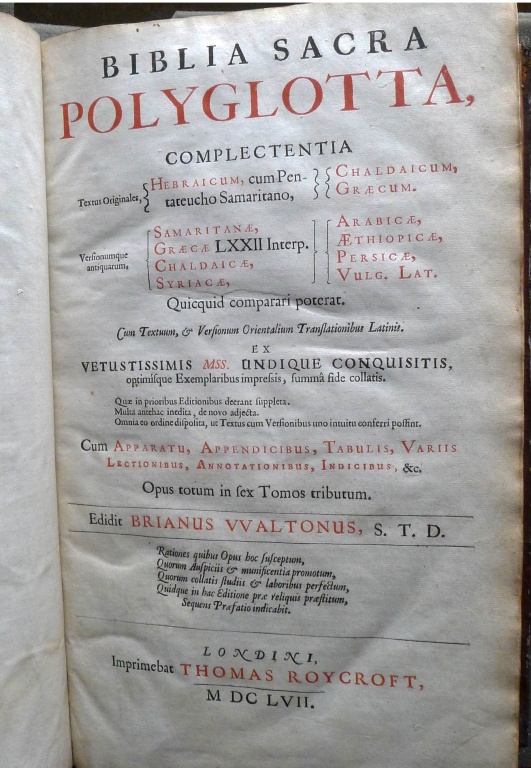

Giacomo was an omnivorous bookworm, with a photographic memory and a love of languages. He taught himself Greek and Hebrew from Dr Brian Walton’s (former Bishop of Chester) 1657 polyglot Bible, printed in London with a dedication to Cromwell, the Lord Protector and effective ruler of England in the absence of a monarch. After the Restoration in 1660 Walton tried to get back as many copies as he could and replace the dedication to Cromwell with one to King Charles II.

Monaldo Leopardi was a political conservative, though apparently he declared his support for Napoleon and thus protected his family and library, and I wonder whether he was aware of, and what he thought of,Walton’s Bible’s chequered history.

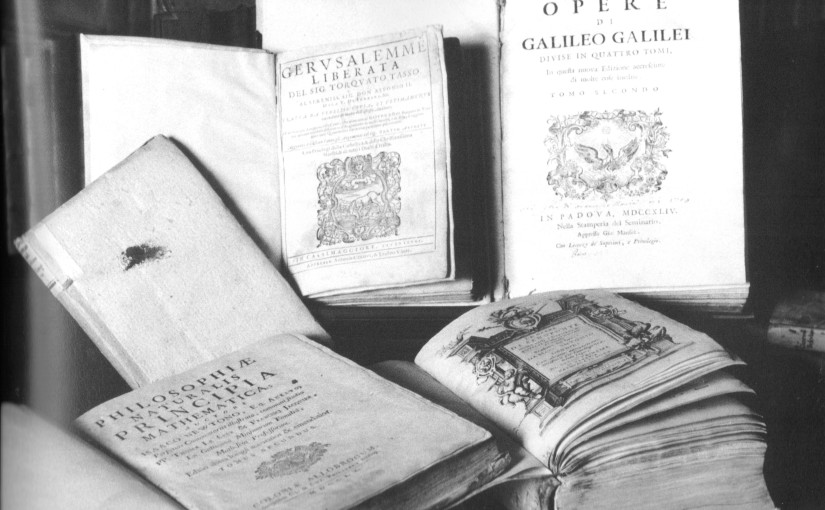

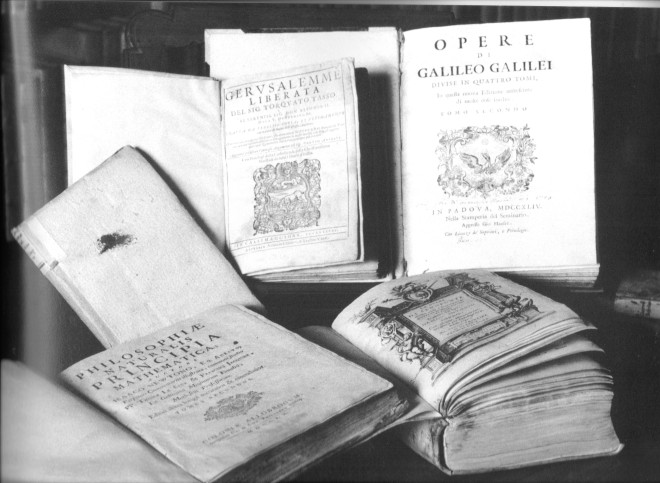

The books in the photo give you a good idea of Giacomo’s wide-ranging tastes, though I hope they were only arranged like that for the photograph.

Monaldo doesn’t seem to have had a librarian. Who needs a librarian when you can get your children to do the cataloguing? There’s nothing new about getting your readers to volunteer, and this seems to have been the way Monaldo related to his children. We are certainly supposed to come away with the impression that they quite enjoyed it.

In his poem “A Silvia”, Giacomo does say, “Io gli studi leggiadri Talor lasciando e le sudate carte”, which Galassi translates as “Sometimes I left the cherished books and labored pages”. I’m relieved to know that the poet did have other interests.

So was Giacomo Leopardi a librarian’s ideal reader? Or would he have been a bit of a know-all. I’d love to know what you think.

Macerata’s historic Mozzi-Borgetti library

We were strolling round Macerata with no intention of visiting its library. I assumed it would be chiuso per restauro (closed for restoration), the three most important words for any bibliophile in Italy. However, we spotted it and I said to the Chelsea Fan, “Let’s go in!”.

Although he doesn’t speak Italian and is only generally interested in libraries and early printed books, he was up for it. We asked the staff at Reception if we could see round, they found another member of staff who was delighted that anyone was interested in his beloved library, and off we went.

As we had given no warning, he didn’t get out any books for us, but he showed us the fine rooms in which the historic collections are housed, and indeed the rooms are worthy of the books they hold.

The library was founded in 1773, though it is actually much older than that. As so often in Le Marche, it is based on the library of a religious order, in this case the Jesuits, who had been suppressed by Pope Clement XIV also in 1773. He gave their library to the Comune of Macerata to form a public library. The library was actually opened in 1787, after it had been given a suitable home (sede confacente), which I think means that its original home was refurbished, and the collections had been enlarged.

The Jesuit library has been added to over the years by various benefactors and bequests, and Macerata Library now consists of about 350,000 volumes. These include about 300 incunables, which we weren’t able to see. Actually the British Library’s Incunabula Short Title Catalogue only lists 269 hits for the keyword Macerata. Where are the others catalogued? The earliest is an Apuleius, printed in Rome in 1469, one of only about 53 in the world. No other comparable Italian communal library has a copy, and there are only eight in Britain.

And a very fine home it is. The Chelsea Fan had to take these photographs discreetly, that’s why there aren’t many of them.

In a very English way I didn’t quite like to ask what the hanging object was doing there; there were similar objects dotted about and we assumed they represented some sort of project or exhibition. A bit incongruous, but certainly creative.

Cardinal Pallotta supported, and Pope Pius VI subsidised, the enlargement of the library between 1773 and 1787. Would that some of the comuni which took over conventual libraries after Unification had received similar help! See the passage about Mondavio library in my post On the trail of incunabula in central Italy .

You can’t really see the sixteen medallions along the top of the bookcases; they portray philosophers and men of science, in keeping with the Enlightenment grand plan of the first librarian, Bartolomeo Mozzi.

How many English public libraries have a ceiling like that? A few, maybe.

This was the last photo the Chelsea Fan was able to take. After our tour we bade a warm and grateful farewell to our kind guide, and I resolved to be more systematic about my library explorations in future.

Rare books and the Franciscan special collection in Ostra Vetere : Part II

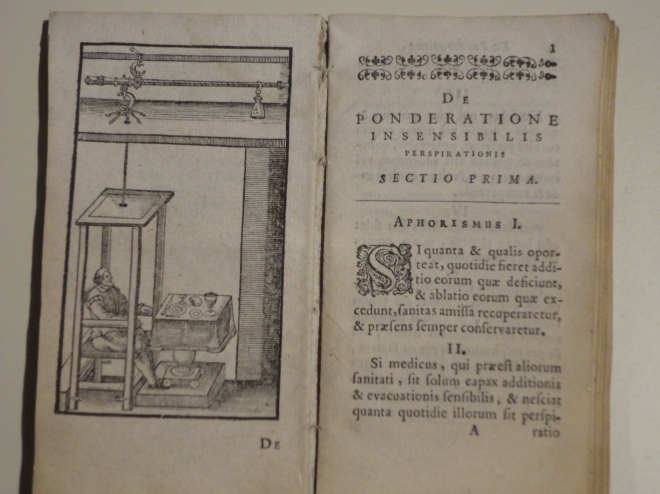

The man in the weighing chair is supposed to be a portrait of Sanctorius Sanctorius himself. The British Library‘s version of this is missing its frontispiece. I was reluctant to include a picture of a book published by Vlacq, who was a mathematician as well as a publisher, and published a book of logarithm tables. How well I remember throwing my log tables into the bin as I left the maths O level exam hall. (Why did I assume I’d passed?)

Rare books and the Franciscan special collection in Ostra Vetere

I enjoy using the British Library‘s Incunabula Short Title Catalogue (ISTC). If you know Le Marche, try typing in the name of a comune and see what comes up. Ostra Vetere has 80 incunabula. That’s about one for 42 inhabitants. You can also find some amusement in seeing what other large and famous libraries have copies of little Ostra Vetere’s books: Bodley and the British Library have copies of Marchesinus’ 1489 Mammotrectus.

The library also has a 1481 Mammotrectus, printed in Milan by Leonardus Pachel and Uldericus Scinzenzeler, but I couldn’t photograph it as it wasn’t on display. In fact they hadn’t displayed any other incunabula.

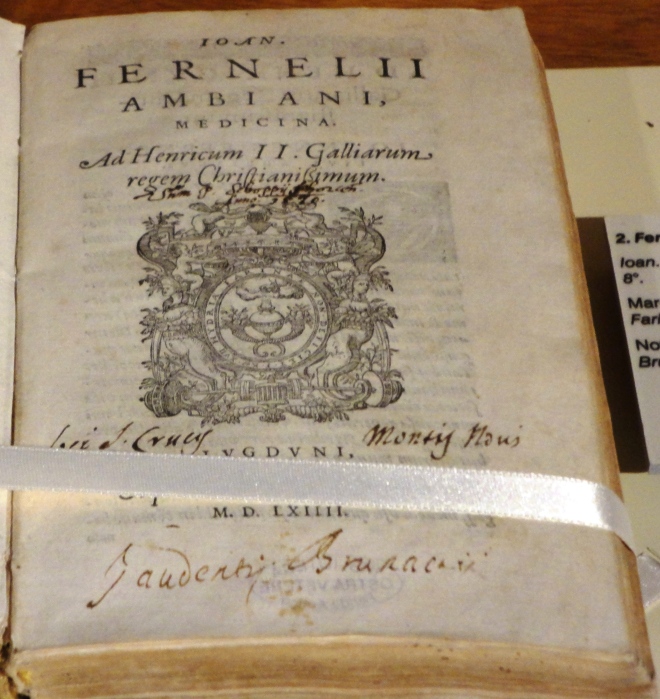

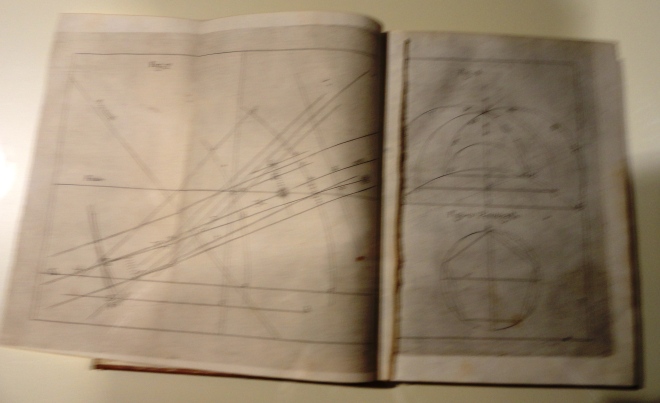

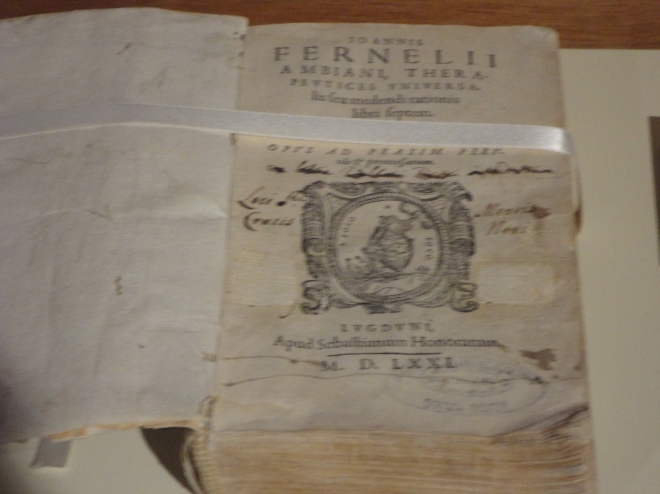

Ostra Vetere’s collection of antiquarian books derives from the Frati Minori, or Franciscan Friars Minor, whose collection the comune took over at the time of the unification of Italy, when many religious houses were suppressed, as happened in Mondavio. As you would expect,the friars had many medical books, for they were expected to doctor the townsfolk. In my previous post I showed you one book by Jean Fernel, and here is another.

Some pictures of the rare books in Ostra Vetere’s library

On the trail of incunabula in central Italy

The Marche region of central Italy – about one third down the Adriatic coast – is full of small, fortified hill towns. It is an area I have come to know well through regular holidaying and, as a librarian, I was intrigued to start investigating some of its small, semi-forgotten book collections.

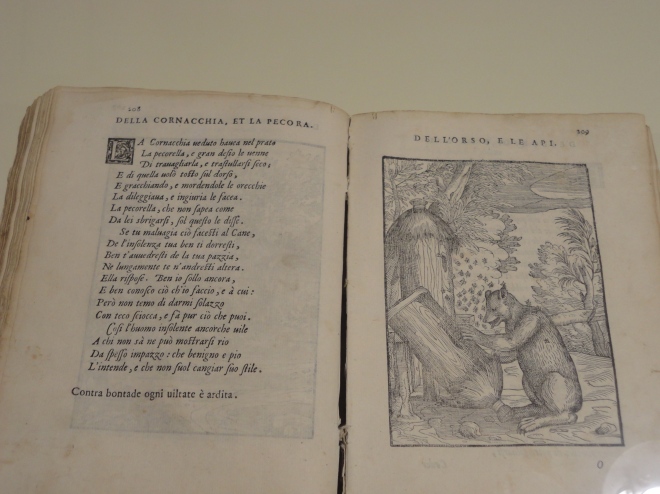

My starting point was the public library in Corinaldo, a small town (pop. 5,200) about fifteen miles inland. In the local tourist office I had already bought a couple of books (Pongetti, below) which referred to the communal library’s collections of antiquarian books, and I was keen to have a look at them.

They turned out not to be on display, but the helpful librarian, D.ssa Monia di Cosimo, welcomes interested visitors and will show the collection to you on request. It includes some 16th century books or cinquecentine as the Italians call them, which have recently been conserved by the Cappuccini friars at Fabriano, a centre of paper-making for hundreds of years, an hour’s drive away from Corinaldo. The province (the next tier up of local government) helped to fund the commune (basic unit of local government) to restore these books.

A few years ago in the regional capital, Ancona, I had seen an exhibition, Collectio Thesauri, displaying, among many others, a book from an even smaller commune, Mondavio (pop. 3,840) across the valley from Corinaldo. On visiting, it turned out to have many more antiquarian books, (about 1,300 from 1450-1800) of which a few have been conserved and displayed in glass cases in the museum. Opening times are few and far between, but the helpful staff may well open up for you specially.

Fascinated by this, and by the contrast between these communal libraries and British branch libraries serving similar-sized communities, I began to dig a bit deeper to find out why and how two small communal libraries came to own significant collections of antiquarian books, always bearing in mind that Italian campanilismo, or pride of place, means that no locality, however small, is willing to surrender any part of its heritage to a larger body, however much more (allegedly) fitted for stewardship.

Until the unification of Italy in 1860 the Marches were part of the papal state and thus hosted many religious houses, many of which in turn had significant libraries. After unification, most religious orders were suppressed and their property passed in many cases to the communes.

The Marches have also benefited from the enthusiasm for book collecting shown by private individuals, be they priests or laymen. In some cases, these collections were to raise money for the collectors’ families, and dispersed. Most of Corinaldo’s aristocratically-owned books are thought to have come to the library via second-hand booksellers. Sometimes collections were donated to the collector’s townsfolk; but not in Corinaldo or Mondavio.

Corinaldo’s antiquarian collection reflects its character as a community dominated by a few aristocratic families and the Church. It consists of 17 titles (18 volumes) which used to belong to the town’s aristocratic families, and 25 titles (37 volumes) from the Cappuccini convent. These have been catalogued by D.ssa Francesca Pongetti in the two publications which I bought locally.

Turning first to the secular collection, the libraries from which these books come were the product of that love of book-collecting mentioned above. This is exemplified by a 1584 Horace which belonged to Tommaso Ciani (1812-1889) and which bears on the fly-leaf a verse exhorting the book “so much loved by me,” if lost, to tell its new owner that it wants to return to its lost owner Tommaso (Quintus Horatius Flaccus: Omnia poemata. Venice, Giovanni Griffo, 1584.) (Pongetti 2004).

The collection does include one example of an individual book donation; Tommaso Boscherini (active 1681-1725) gave the citizens of Corinaldo his 1686 “Labyrinthus Creditorum” (a treatise on voluntary liquidation) by Salgado de Somoza, a 17th century Spanish jurist, printed in Venice by Giovanni Battista Tremontini in 1686 (Pongetti 2004).

Although the Cappuccino convent in Corinaldo was suppressed after unification and the friars had to leave in 1867, they found temporary shelter elsewhere and were allowed to reclaim their home in 1874. Nevertheless, some of their books did find their way to the communal library.

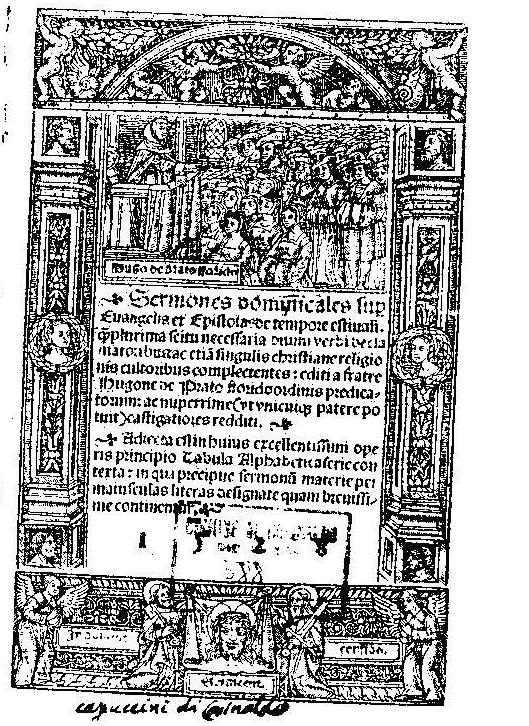

The collection reflects the interests of the friars and the purpose of the library. There are a number of religious texts, including Bibles, theological treatises, and, as preaching was an important part of their duties, collections of sermons. Among these is the library’s oldest book: a collection of sermons by Hugo de Prato Florido, printed in Lyons by Antonius du Ry in 1528. (Pongetti 2002.)

In contrast, Mondavio’s collection of antiquarian books derives from one source only – the Cappuccino convent of Mondavio, which, lacking the gentry support which the Corinaldese convent enjoyed, was definitively suppressed in 1867. Its library (about 2,800 books) was offered to the commune of Mondavio. They decided to take it in 1868, and, as a small commune without the dominant gentry families of Corinaldo, they seem to have bitten off more than they could chew. The collection as a whole has never been fully open to the public. Nowadays, some of the most valuable and interesting books are conserved and on display (not for reading), but the rest of the collection is closed to the public. Its incunabula and cinquecentine have been catalogued by D.ssa Barbara Lepidio as part of her degree thesis, of which she has kindly sent me a copy, but which is not widely available. In 2006 the commune did ask the province for Eur. 4000 to publish a catalogue of incunabula and cinquecentine (presumably Lepidio’s), but without success.

The library boasts 7 incunabula, including a Latin version of an Arabic treatise on medicine, the Al-Hawi of Rhazes: (Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakarija: Liber expositio; medecinarum simplitu elhavi [sc Al-Hawi]) printed in Brescia in 1486 by Iacobus Britannicus).

There is also a complete Seneca printed in Venice in 1492 by Bernardino de Coris of Cremona, and a prologue to the letters of Marsilio Ficino printed in Venice by Matteo Capcasa of Parma in 1495. (Lepidio.) Generally, the collections reflect the spirit of the age in which they were acquired, and these fifteenth century books reflect the humanistic spirit of enquiry of the period – even to the extent of including a book by a Muslim, albeit a standard medical text-book.

For full details of the incunabula see the British Library’s Incunabula Short Title Catalogue an indispensable research aid.

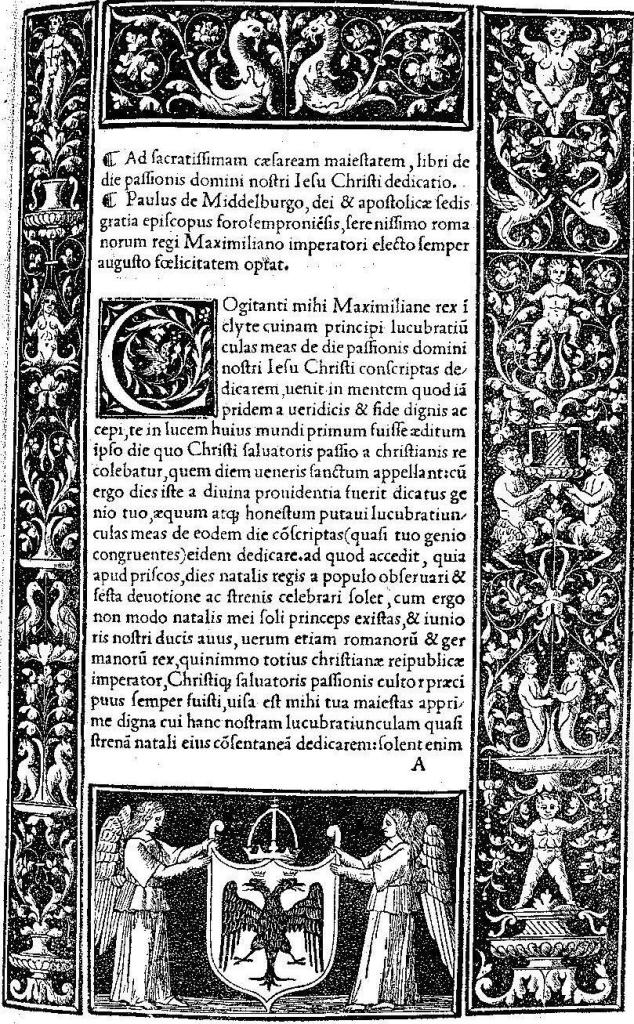

Mondavio library also has a fine example of a book printed locally in the Marches, in 1513, by Ottaviano Petrucci of Fossombrone. Petrucci was one of the earliest printers of music; born in the small town of Fossombrone, he worked in Venice and moved back to Fossombrone in 1511, where his first book was a long and complex treatise, familiarly known as the Paulina, by the local bishop, Paolo da Middelburg, on the calculation of the date when Easter should be celebrated (Mei).

Considering the history of these two small Italian collections, one naturally asks “Is bigger better?” Does a collection need to be owned by a large authority, to be properly looked after? I would answer: “not necessarily”. Small collections mirror their local communities and would lose their uniqueness if moved or merged. Belonging to a large organisation is no guarantee that any special collection will be cherished as it deserves. With help and support from higher-tier authorities, and awareness and support from their citizens, the small towns of the Marches can flourish as proud owners of precious books.

Bibliography

Lepidio, Barbara. Tesi di laurea: La libraria dell’ex-convento dei Cappuccini di Mondavio – edizioni del XV e XVI secolo dal fondo antico della biblioteca comunale di Mondavio. Urbino, Universita degli Studi, 2001.

Mei, Mauro (ed.) : Collectio thesauri delle Marche; …Vol. II; l’arte tipografica dal XV al XIX secolo. Ancona: Regione Marche, 2004.

Pongetti, Francesca: I Cappuccini nella diocesi di Senigallia e il valore singolare della libraria e del convento di Corinaldo. Fano: Grapho 5, 2002.

Pongetti, Francesca: La “Marca” e le famiglie nobili e notabili di Corinaldo. [Fano:] Futura, 2004.

Thanks to Margaret Curson of Brighton and Hove Libraries, Monia di Cosimo of Corinaldo’s Biblioteca Comunale, Barbara Lepidio, librarian at the University of Urbino, and Carol Marshall of Hampshire Libraries.